The female character that makes men uncomfortable

Freya Akselsen and pop culture's strong woman problem

The Problem with “Strong Women” in Popular Culture

Popular culture has a problem with strong women. Not with strong women themselves — but with how we imagine them, and how they’re usually depicted on screen and page.

The Four Archetypes

The representation is painfully narrow. In mainstream media, strong female characters tend to fall into just four categories.

The Stereotypical Feminist

This is the least developed type — a character who exists as a mouthpiece for whatever’s trending in feminist discourse. These are the fakes, the checkbox characters created to give the appearance of answering society’s demands. The demand is real, but the male screenwriters clearly didn’t put in the work.

Captain Marvel is a perfect example. A massive budget spent on marquee actors and marketing, all for a massive disappointment.

Captain Marvel’s defining traits are literally just physical strength and perpetual anger. She’s completely forgettable, her story paint-by-numbers. Her entire journey toward empowerment consists of punching the male villain while shouting a few feminist slogans about strong women in his face.

The Traumatized Woman

Think “The Girl on the Train” or “The Luckiest Girl Alive.” One struggles with alcoholism after her divorce, the other is dealing with the aftermath of assault and terrorism. These aren’t bad stories — they’re important stories that reflect a harsh reality many women recognize in their own lives.

But these stories alone can’t capture the full range of what strong women can be.

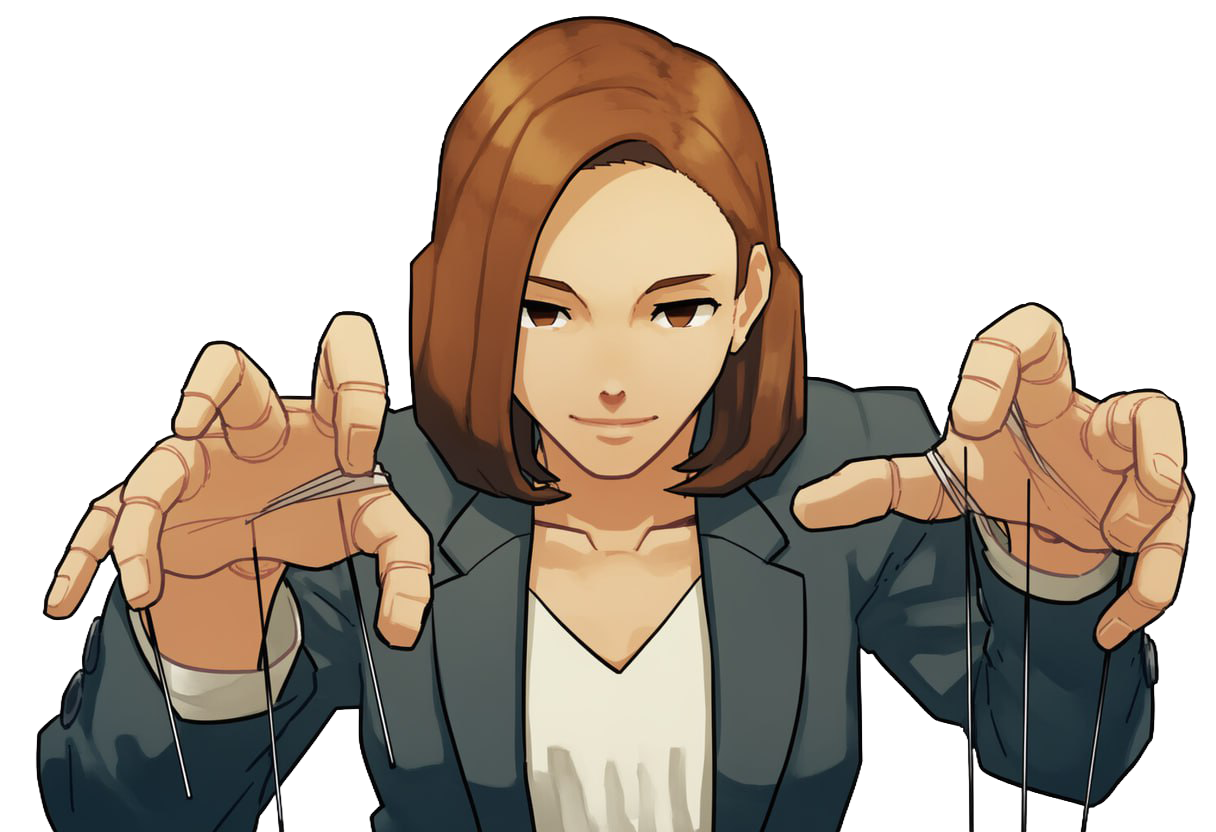

The Psychopath

This is actually the most interesting archetype. Psychopaths are clever, inventive, and you can build genuinely complex plots around them.

Take “Gone Girl,” where the protagonist orchestrates an elaborate revenge scheme to destroy her husband’s life and bend his entire existence to her will.

In one sense, the psychopath is the perfect “strong woman”— she can never be a victim of manipulation because she’s always the manipulator. She doesn’t care about conforming, can’t be guilted into submission, making her essentially immune to patriarchal pressure. This is the ultimate female power fantasy.

But here’s the catch: fictional psychopaths are remarkably palatable to patriarchal culture. Being the object of obsession for a woman who also functions as a second mother, now with sexual availability thrown in — that’s a male fantasy. Especially when these women only exist safely contained within TV shows and novels.

The Femme Fatale

Beautiful, brilliant, endlessly charming — she weaponizes every advantage to manipulate men. She’s taken patriarchy’s leash and turned it back on itself.

Another male fantasy. And an impossible ideal for real women—who among us can always look flawless, always have the perfect comeback ready, and casually juggle admirers? In reality, women are more likely to get stuck splitting the check than receiving hearts on silver platters.

The femme fatale is also always young. There’s no other kind. Real women age.

What About Women Who Don’t Fit?

Our novel’s protagonist, Freya Akselsen, was one of those women. And she triggered a fascinating response in male readers — specifically those with conventional masculine socialization.

Freya Akselsen: The Ideal Protagonist

Here’s the thing about protagonists: they need agency. The drive to change their world. That forward momentum that makes a story move.

A passive hero can’t carry a narrative. In our culture, it’s probably easier to imagine men as naturally agentic because that’s what masculine socialization emphasizes. The adventurers, super-spies, politicians, and detectives are usually men.

But I wanted a female protagonist. No trauma backstory, no dark past to overcome, no desperate need for love. So we chose the perfect candidate — a trope-smashing Instagram business coach. Freya Akselsen.

Freya doesn’t just dispense productivity tips and tell everyone to read “Atomic Habits.” She’s that rare breed who actually implements new habits before finishing the last page. How many habits have you adopted after reading self-help books? Probably zero. Freya? At least ten.

“Fake it till you make it”— that’s Freya’s whole philosophy. And her name isn’t just symbolic (I wrote about that in an earlier piece) — she uses self-development advice as a tool for self-mythologizing.

When things go wrong, she pivots to positive thinking. When she’s short on ideas or information, Freya doesn’t overthink it — she just acts.

Freya isn’t stupid, but she’s not a genius either. No special talents like being a chess prodigy.

But Freya Akselsen succeeds because she takes one more step than everyone else, and gets up one more time after failing.

Despite being the perfect protagonist on paper, male readers hated her. Let me tell you why.

The Patriarchy Litmus Test

Freya Akselsen is no femme fatale. She doesn’t leverage her looks and charm to ensnare men’s hearts. She doesn’t actively exploit male weaknesses to get what she wants.

It would have been prudent to respond neutrally, diplomatically, as befits the confines of the Deep State. However, Freya found herself unexpectedly seething at Mister K’s audacious display of candor over the phone.

“So what do you want from me?” she asked with deliberate indifference. “I don’t understand where you’re heading, Mister K. You’re not taking any risks: I’m sitting with my knight in my cell, as ordered.

Instead, Freya Akselsen is a mirror that forces every patriarchal man to see himself clearly. She’s stubborn, deeply flawed, yet carries herself with tremendous self-assurance.

There must be a reason why, out of all the confidants, Mister K chose you, milady Freya” The dr. Ferdrehels said. “I don’t understand it yet.”

Freya merely shrugged.

“He didn’t choose,” she replied. “It’s just that on the Night of Merge, I chose to save New York and captured the aliens to restore our Future.

Throughout the story, she refuses help when it’s offered—actively sabotages attempts to rescue her.

I could have saved you only by harassing you enough to force fleeing to Texas,” said Mister K, “You would have lived to the age of ninety-two on the ranch.”

Freya slapped the table in front of the curator with a loud clap, trying to sober him up.

“A ranch?!” She exclaimed. “I would never, ever go back to Texas!

She’s nearly impossible to guilt into gratitude.

“I didn’t ask for this,” Freya retorted sharply. “And never asked to be saved.”

And Freya can’t even be called a good person. She doesn’t do anything evil — quite the opposite, her actions are benevolent — but her thoughts? Those are coldly calculating.

Freya acts according to her own judgment, bites off more than she can chew, takes risks. Like James Bond.

If Freya were male, nobody would call him a bitch or a Mary Sue.

A New Type of Strong Woman

Freya is Scarlett O’Hara’s daughter and May’s (from The Circle) older sister.

She’s a fighter, but there’s no terrible tragedy in her past that she must process throughout the story, no journey to reconcile Old Freya with New Freya.

Even the leaked sex tape at the story’s opening — that’s not Freya’s tragedy. It’s society’s tragedy, where an intimate video can cost a woman her confidence, reputation, and career. Not a trial for the heroine, but a litmus test for the reader’s attitude toward her.

Yet Freya Akselsen isn’t a psychopath bent on revenge against men or the world. Men occupy far less mental real estate than productivity hacks. Throughout the story, Freya pursues her own goals—never male attention or love.

“Business isn’t a substitute for a man, and a man isn’t a substitute for your life’s work. A business doesn’t need to be placated like a lover. And the right business,” Freya added with a smile, “will always work for you—which, you have to admit, gives it a distinct advantage over a man.”

Freya doesn’t even call herself a feminist. Feminism is just another tool in her kit, something to monetize and build an audience with while breaking into real business.

The trolls’ moms gave them no more than five dollars for school. So they were utterly crushed by a counterattack from the very heart of Freya’s audience, summoned by the fan groups on Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram. Rushing to their idol’s defense were the stay-at-home moms, the nail techs, and the college girls from the middle of nowhere. The housewives who’d swapped their ladles for smartphones at the rallying cry of the digital age. And men who craved attention from all the aforementioned women, so they started posing as “one of the good ones” and didn’t notice how they were spending twenty bucks a month on Freya.

Not the best audience if you’re a serious woman sharing secrets of real success, but loyal. And loyalty means a lot in real business.

Freya lives in a world built on masculine notions of success, where she could easily become just another casualty. Instead, she doesn’t just accept the rules — she internalizes the success philosophy so completely that nothing else matters. Not a thing, not a person.

Why Freya Terrifies Male Readers

Because a woman like Freya strips men bare. Like standing before God, they appear before her as at the Last Judgment, with nothing to offer but their actual personality and merit.

The femme fatale legitimizes male weakness by exploiting it. Patriarchy lets men feel desired even if only momentarily, for mercenary reasons. Being used by a woman who outshines you isn’t humiliating when you’re still wanted and needed.

But Freya Akselsen? She simply doesn’t see mediocre, unremarkable men. Despite being far from perfect herself.

She leaves them no way in.

Let's confess: we cooked with Freya fr