When the protagonist becomes the player

We wrote 3 million words to learn how to finish stories

The truth nuke of today is that character-driven fiction writing and game design are, in fact, the same.

It might not make any sense now, but bear with me. I really liked the feeling of understanding this idea, so WILL you.

Ever since we started writing A Plan of Silence, I thought it’d be cool to turn it into a game—without any specifics. And now, when literary agents showed us the door and we’re actually building a thriller dating sim to promote the novel, I realized we are blessed.

And our inexperience blessed us.

Because to write the hefty brick of 128k words that is The Plan, we had to write 3 million words of drafts. Three completely different branches from beginning to end, and endless offshoots. Yes, I counted all our Discord records. Yes, we wrote directly in Discord. Yes, we’re not like everyone else, and I’m going to capitalize on that anyway.

Now, when data is the new oil, having such a massive archive of hand-written material is a blessing in itself. But back then it was a genuine curse.

Because neither the concept, nor the setting, nor even the plot foundation of the novel fundamentally changed during all that time—though they improved significantly. Years of research didn’t vanish. We already knew dramaturgy well, and the art of building emotional roller coasters so that the reader could do loops and barrel rolls. To finally complete the story, however, we had to learn an entirely different skill.

We had to learn to listen to the character’s true choices.

Because it turned out that a novel is the same thing as a game. Where you, as game designer or game master, build a plot that the player’s choices will reveal. You create challenges for the player, simple and hard ones; you build tension through rising stakes, you let the player recharge with breathing room. With points of no return, where choices transition into consequences, you create a sense of progress. And you build an experience that changes the player at the end of the day.

Sounds obvious, until you realize the “player” of the novel isn’t the reader—it’s the main character.

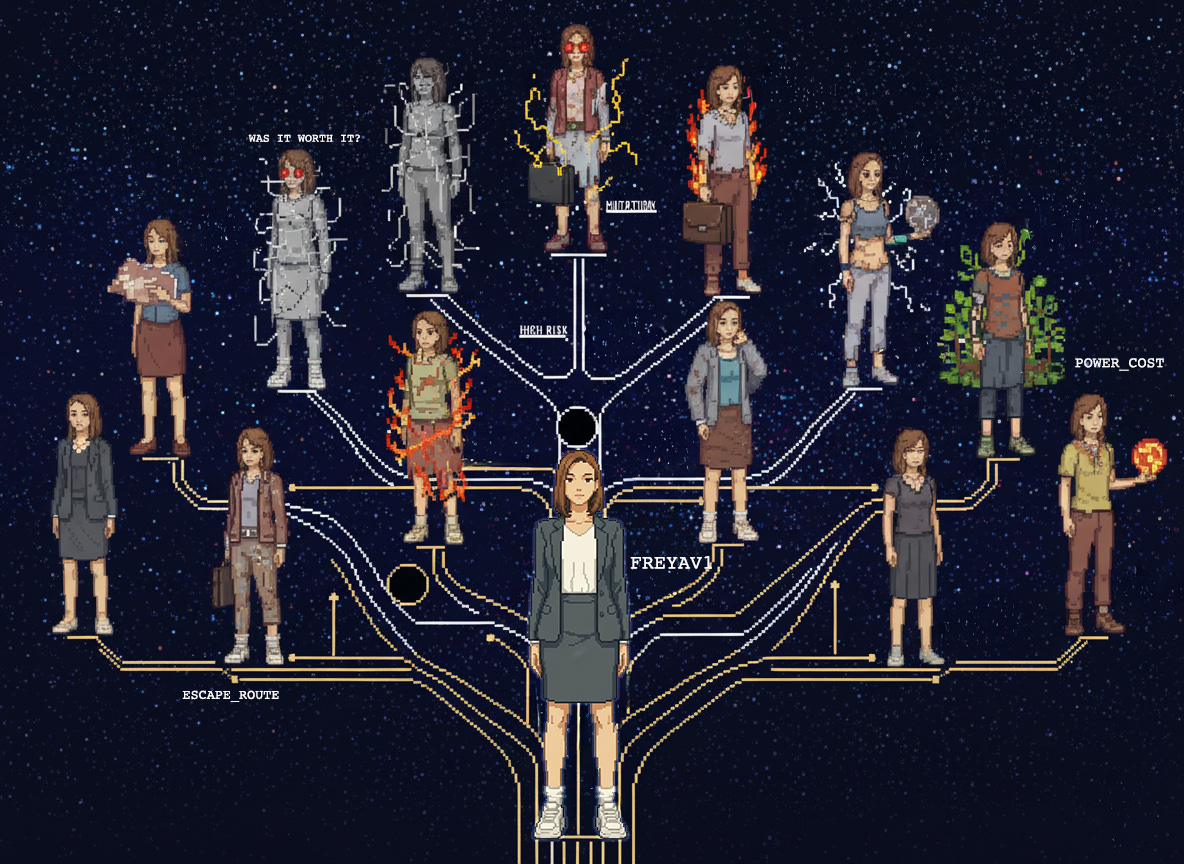

Because just like a player, our Freya—the star of The Plan—went through every story branch. Stress-tested our lore and setting. Questioned doors that wouldn’t open, and exploited our oversights to phase through walls straight to the treasure, without fighting bosses. Freya cheated to win, then got upset and abandoned the plot if she managed to cheat successfully. And she also lost interest and quit our novel’s game if the trials were too brutal, like Dark Souls.

I’m glad she turned out loyal and stayed with us to the end.

And that’s all not an exaggeration.

Our story crises and writing blocks were caused by putting the protagonist in conditions where she couldn’t move. We burned ourselves out because we threw Freya into completely inhuman, visceral trials that broke her worse than random deaths in a game from a particularly teeth-grinding parkour level. We wrote two branches of 30 chapters each that couldn’t finish. Because in the first one, Freya had no ability to influence her fate—and in the second, fate catered to her too much.

And when we tried to force her down the prepared rails, she just “shut down.” The way neural networks or—God forgive me—large language models can shut down by sending empty responses when they don’t want to respond to a user’s stupid prompts. We were bad users. She was good Freya.

And then, we understood how it works.

A game is built around the player—and the game designer can’t change the player, because they don’t choose one to begin with. All the game designer can change are the rules and mechanics of the game. In the game, there must be skin, but also the relief and gain. A game is medicine against the world’s injustice and meaninglessness, through being the complete opposite of the world. It is the art that life imitates.

And understanding this, we wrote 32 brilliant chapters in one breath.

And now, when we’re making a game, this helps from a completely unexpected angle. We have material about absolutely every plot development. Answers to every “why” question. Knowledge of all extreme motivations. Because Freya experienced everything.

In the novel, Freya resolves the issue with her ex very quickly when he crawls straight out of the drain to save her from the Deep State—but we know how he got there, and what lives on the other side of the deep concrete walls. Freya chooses only one person from everyone she met—but we know how their story would have developed all the way to the alcove (more often to the grave; but in The Plan’s universe, the grave is just the beginning).

In the novel, the player was Freya—and our task was to capture her unique choices.

In the game, though, the player is you. So only you get to decide whether she saves the world or dooms it. Fights the aliens, or runs and hides, tossing her hero sword in a trash can (like she did in the novel). Hands her ex over to the Deep State, or teams up with him against the Illuminati. Whether the talking animals will speak—and what their secrets will cost her.

Honestly, I like this even more than coddling Freya. Because it gives real creative freedom. Even the freedom to destroy everything—something no novelist can afford, because a collapsed story won’t get published unless you’re Kafka.

Without coddling Freya, though, I would never have become the best version of myself and wouldn’t be making this game.

And here’s a Freya quote that appeared early enough, and that I should have paid attention to much sooner.

I have a plan. I know how to save everyone—people and the Silence alike

This was impossible, according to the plan we’d set.

But Freya did it anyway.

And that became the new Plan.