Your author brand is fake (and that's fine)

Identity explained by a 2,000-year-old paradox

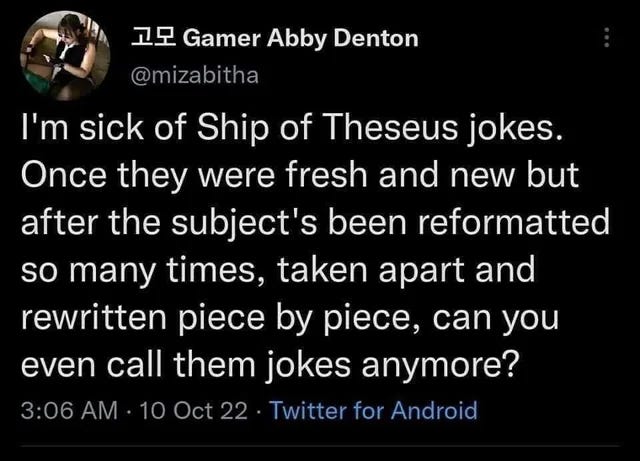

What is identity? And authenticity? I found myself facing these questions through, unexpectedly, the classic Ship of Theseus paradox.

The puzzle starts simply enough: if every plank on the Ship of Theseus is replaced over the course of a century, is it still the same ship?

Can physical continuity really be the measure of identity? I had two arguments against it. First — humans are multidimensional beings extended across time, all versions of us existing simultaneously. More practically: we’re not made of the same matter we were ten years ago. So why should the ship’s identity be tied to its material components?

No, the ship’s true identity isn’t in its physical substance, but in its non-physical attributes. It’s the persistent idea of the ship, its continuous history, and the collective myth surrounding it that define what it actually is.

Then the thought experiment gets complicated: a second ship appears, meticulously assembled from all those old, discarded planks. Which one is the real Ship of Theseus? The planks, after all, carry history. And history is part of the myth.

But identity is fundamentally a social construct. Its authenticity isn’t an intrinsic property of wood and nails — it’s a status granted by collective belief, by the people who recognize its story and place in the world. Who knows about the old ship? Did it feel legitimate enough to claim that myth? Who had the, forgive me, marketing on their side?

That’s how I arrived at the plot twist: an author’s public identity works exactly the same way. It’s a constructed myth, a narrative built over time. The “real” or “authentic” version in the public’s eyes is whoever tells the most compelling story — whoever builds the myth the audience chooses to believe in and follow.